TOUR DE FORCE

In his first 16 months as a pioneer Kimberley tour leader, Sam Lovell showed 400 people his country.

There had been just three people on the first tour nearly 40 years ago, but word spread like wildfire. “People came from everywhere around the world but the majority were from WA … doctors, nurses, farmers, school teachers …” says Sam. “They learned everything. Aboriginal history, white history, rocks, plants and water holes.”

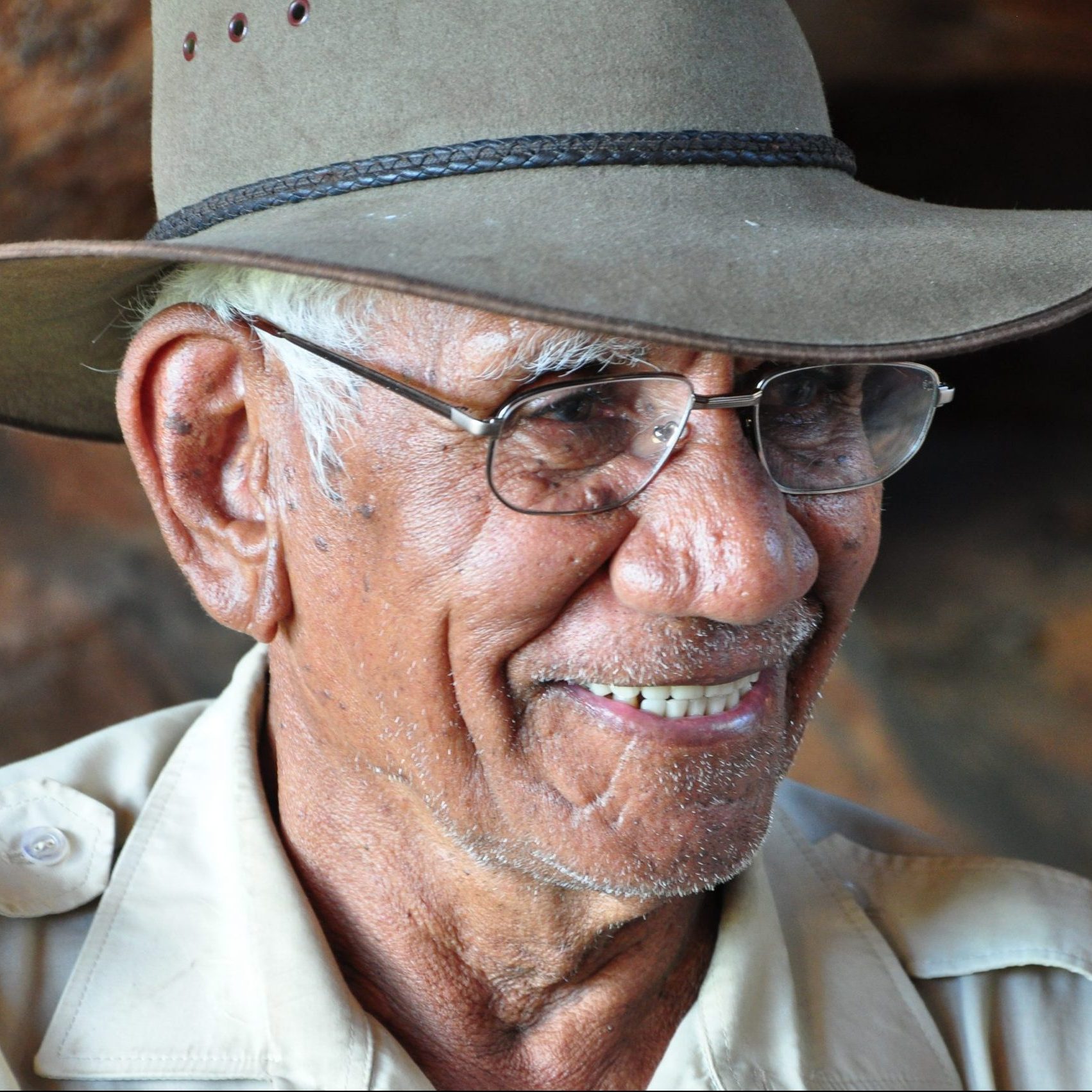

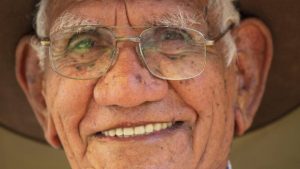

Sam, 87, is a patron of the WA Indigenous Tourism Operators Council, which represents and promotes West Australian Aboriginal tours locally, nationally and overseas. And he says there’s a future path for Indigenous people in tourism. He praises, for example, the introduction of the Aboriginal Ranger Program in national parks.

Sam Lovell. Nambung Country Music Muster, Nambung Station. Credit: Stephen Scourfield/The West Australian

“People today are very interested in Aboriginal culture,” he says. “Before that, no-one was interested. “When we started, we didn’t know anything about tourism,” Sam adds. They set up in an eight seater bus, “and paid cash for everything”. For the first 12 months they did one-day tours, then added six, eight and 16-day tours.

He says his wife Rosita was greatly helped by Peter Kneebone (who would be president of the Shire of Derby West Kimberley) and filmmaker Peter Storey. Sam says: “Rosita was the main worker — the main booker and in charge of cooking and stores. I did all the talking and mechanical work — heavy things.”

STOCKMAN SAM

Sam was born in 1933 on Calwynyadah Station in the Kimberley and taken by the government when he was three. Sam never saw his father Jack or mother Biddy again.

Like hundreds of other Aboriginal children in the Stolen Generation, he was sent to Moola Bulla, a government-run station 20km west of Halls Creek, in a different tribal area, with a different language.

He says there were 300 kids there from somewhere else, but they were accepted. “The old boys used to teach us how to make spears and boomerangs,” he says. “They were great.”

The station was run by Native Affairs, says Sam — but more specifically by superintendent Alf George. He was a tough, formidable man for the boys, but looking retrospectively, Sam says: “I think he was the greatest man I have ever seen. He took control of everything from stock to people. He had to be hard with some people, and was different with other people.”

At four or five years old, Sam was learning to ride on billy goats. He got his first job on Moola Bulla when he was nine, taking his lunch and a tin of petrol and walking 8km to a windmill to pump the pump. When he was 10, he was given a job boundary riding on a horse.

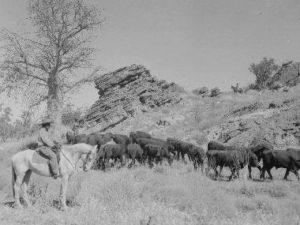

“We all had to learn stock work too,” says Sam. “We used to go out eight months a year and only come to the homestead when we went to the races.”

At 12, he became apprentice to saddler Charlie Fletcher. There were 100 saddles to be made each year. There were 800 horses, five stallions each with 50 mares, and 60 riders in the muster camp.

Full-time horse breaker Pincher branded and cut the colts, then rough-broke them. But it was up to the boys to “finish them off”, and make good, gentle riding horses of them.

“Everyone loved handling stock and riding horses,” says Sam. The Indigenous boys were competitive, and keen to become great stockmen. “Station life is great for a young fella who wants to find himself. You learn to respect yourself and respect others.”

They also learnt charcoal and lime burning and tannery.

Stock being mustered by Aboriginal stockmen on Fossil Downs Station in the Kimberley. Credit: Supplied

It was a man called Tiger’s job to kill and butcher a bullock a day to feed everyone, and the hide was thrown over a log and then scraped with a big knife to get the meat off. Then it was soaked in a lime pit, and the hair scraped off and collected to use as saddle stuffing. The hide was soaked in warm water with snappy gum bark to give it a tan colour. The animal’s fat was boiled in a 44-gallon drum to make soap.

“I think we were very lucky to see all them things and do the work with them,” says Sam.

By the age of 14, Sam was a qualified saddler, and one of his saddles and packs is on display in the museum in Perth.

Then, in 1950, Bluey O’Malley was looking for drovers, and got Sam on the team to take bullocks to Glenroy Station. The manager there, Walter O’Connor, offered him a job. “I had no say in the matter,” says Sam, but when superintendent George was asked, he gave permission, and Sam worked there for five years, becoming head stockman when he was 17.

“We had to mature and take a big responsibility at an early age,” he says. “Walter O’Connor was the best man I ran into. He told me, ‘Be your own man and don’t think anyone owns you’. He taught me things and sometimes he gave me a growling, but he told me why.

“He taught me to tail cattle; keep them quiet. He said, ‘There are drovers and there are drivers’. I am very grateful for all he did.”

From 1955, there followed good years on the great Kimberley Downs and Napier Downs stations, but in 1960, Sam was on a horse he couldn’t stop, which jumped into a dry billabong, fell, rolled on him and he suffered a serious back injury. He recovered, worked on, but two years later a bucking horse broke his back, and Sam, newly married to Rosita, spent nine months in Perth in hospital.

When he returned to the Kimberley, Joe Elliott on Yeeda Station offered Sam and Rosita and their young son a house and three meals a day, and said, “You don’t have to work”. Sam still busied himself checking bores, chopping wood and watering — but knew it was the end of his stock work.

A £70 Bedford truck, its tyres eaten through by white ants, an engine in a box “in a thousand pieces”, would transport him into the future. He rebuilt the truck, and found other work.

There was the bitumen run for the Gibb River Road construction, fencing, yard building, and time managing Ellendale Station, converting from sheep to cattle and testing the stock lick made by David Gray, an important innovation in the mid 1960s.

That whole career on the land had come from his thorough station education at Moola Bulla. Sam says: “When they sold Moola Bulla, it was the downfall of a lot of things for Aboriginal people. They got rid of them in 25 hours — 500 people. They had to walk to Hall’s Creek, and they had no money.

“Then they got government money to live; equal rights a year later; drinking rights a year after that. It was the start of a lot of the problems we have today. These were serious things for our people. These things broke down the culture.”

Sam believes land rights should have been claimed for whole tribes, not individuals. “We have gone off in the wrong direction and there are going to be big, big problems. All the old elders like me are dying off.”

In 1981, Sam, who still lives in Derby, switched to tourism, and put the truck to use for Kimberley Safari Tours.

ORIGINAL INFLUENCER

Just as Sam carefully lists and acknowledges those who have guided, he has influenced others. Including me.

In 1993, I joined Sam and our mutual friend Peter Storey, who died in 2002, for a day on the Fitzroy River in flood. It was a massive wet season — the Fitzroy rose by 24.38m, and we were concerned about Helmut Schmitt, the hermit who lived in a shack beside the river.

We set off in a tinny boat with a Mariner 40hp outboard in the fast-flowing river, dodging through the tops of the trees. It was a fair old hullabaloo.

When we got to Helmut’s camp, the old hermit was living on his quavering roof with his dogs. The pig had been washed away.

“We won’t see him again,” said Helmut.

He didn’t want to come with us, despite the precarious sway of the submerged hut in the flood waters and the possibility of it going right under. He just wanted us to bring back more dog food.

The day was so dramatic and Sam’s presence so steady, that it all found its way into my novel As The River Runs, written 20 years later.

Sam Lovell and Lucy Lemann practise tunes at Nambung Country Music Muster. Credit: Stephen Scourfield/The West Australian

DIRT & MUSIC

There’s dirt and there’s music, and this is the authentic version. Sam Lovell leans over the Martin guitar he bought in America and croons quietly, and then yodels a few phrases. Classic, old-style country. At 87, he’s playing songs off his new CD — his first-ever recording.

“I have been trying to play guitar since the 1940s,” says Sam.

“On Moola Bulla, we weren’t working for money, but someone gave someone an old guitar. When the big boys had finished playing it, me and my mate Paddy McGinty use to grab it and play it in the sheep trough.”

They learnt I Got the Dear Old Aussie Blues, a song by Buddy Williams aka The Yodelling Jackaroo. “The only record we had,” Sam says.

He bought his first guitar in 1950 and started learning Slim Dusty songs. He’s been to the Tamworth country music festival annually for the last 21 years and now he’s finally recorded some songs, with help from Alan Pigram in Broome.

“It took me 80 years to get enough courage to make a CD,” Sam says.

Sam Lovell’s Kimberley Campfire Favourites includes three Slim Dusty songs. And next to it on the table at the Nambung Country Music Muster is a CD by Ken Lindley. I flip it over and there, second on the playlist, is a song called Sam Lovell Story.

And, last Saturday morning, he walked out on stage with Derby musician Lucy Lemann, who previously played with Jam Tarts and is now Mango Mob

Line dancers. Nambung Country Music Muster. Credit: Stephen Scourfield/The West Australian

NAMBUNG MUSTER

Twelve hundred people turned up for the Nambung Country Music Muster last weekend.

The festival was started five years ago by Gloria and Brian White, owners of Nambung Station and Station Stay, in Wongonderrah Road, Nambung — near the Pinnacles, inland from Cervantes.

That first year, 600 people came, it’s grown each year, but this year was capped by coronavirus restrictions.

“Each year we have tried to improve the venue,” Gloria says.

Thursday and Friday were for amateur “walk-ups”, the best winning a spot on next year’s bill.

But these days they are also used to encourage younger artists — this year, like Chelsea White, and Sally Jane, a young singer, songwriter and guitarist from Serpentine.

“We are discovering new talent for our program each year,” Gloria says.

Ginger Cox, Sam Lovell, Ken Lindley and Terry Bennetts at Nambung Country Music Muster, Nambung Station. Credit: Stephen Scourfield/The West Australian

Saturday and Sunday’s line-up are performers booked by musical director Terry Bennetts. Last weekend’s line-up included Red Ochre Band, The Everly Sisters, Ginger Cox, Warwick Trant and Kathy Carver.

The audience pays $100 per person to come to the festival and there’s a warm, “one big family” feel to the muster. People chat in the queue for ice creams, there’s a band of bootscooters in the shed, and a couple breaks into spontaneous dance as Sarah Broome and her band play.

In getting to the festival, Sarah had suffered a vehicle breakdown and had then hit a kangaroo, but her fellow performers donated CDs and books for a raffle to help her weather the financial hit.

“I’m a very, very lucky girl to have such love,” she said from the stage.

Nambung Station Stay is surrounded by national park, and backs on to the Pinnacles Desert. It has limestone pinnacles and the Painted Desert on the station. Brian and Gloria run tours to see these.

Nambung Station Stay is still a working farm, with more than 2000ha of land and 300 beef cattle and 3000 fine wool merino sheep, though it is also a registered Land for Wildlife property. There are kangaroos, emus and “its fair share” of Carnaby’s black cockatoos, says Brian.

“It’s been such dry years,” he adds.

“We only get half our average rainfall.”

Guest accommodation includes a two-bedroom house which can sleep up to eight people, two on-site caravans, and powered and unpowered camp sites. There’s good access down unsealed roads for caravans. nambungstation.com.au

Stephen Scourfield The West Australian

Tue, 3 November 2020 1:34PM