“Australian Rock Art links into a culture that is ongoing and represents one of the longest cultural traditions on the planet. It is amazing to be able to contribute to a research project of this stature” DR HELEN GREEN

A new Fellowship in Rock Art Dating has been awarded to the Kimberley Foundation Australia who has bestowed it on Dr Helen Green, a post-doctoral scientist at The University of Melbourne and a member of the Rock Art Dating research team. RAA Director Professor Andy Gleadow has described Dr Green as ‘a career scientist of exceptional merit and an emerging research leader.’

The $740,000 Kimberley Foundation Australia Fellowship in Rock Art Dating is funded $600k by The Ian Potter Foundation and $140k by RAA. Helen will examine mineral coatings that have developed over time on rock art surfaces in the Kimberley, and identify which coatings might be dated using the uranium series dating method. The study will contribute to a multi-disciplinary project investigating the history of human origins in Australia and indigenous cultures in the Kimberley. Known as the Rock Art Dating project #2, it commenced its 2nd phase last month following a successful 3-year funded research period where technical firepower was the focus. It too is funded by RAA ($400k over four years) and the Australian Research Council also re-committed to the innovative project with an additional $880k to be spent over four years.

Helen will work closely with the Traditional Land Owners, the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation and the Rock Art Dating team at The University of Melbourne, led by Prof Andrew Gleadow, as well as colleagues including ARC Laureate Prof Jon Woodhead and Prof Janet Hergt as well as Dr John Hellstrom, Dr John Moreau and others.

Born and bred in Manchester, Helen has had a life-long interest in Australia. Her great-grandmother was a ten-pound pom, arriving in South Australia in 1961. With her great-grandparents, uncles and first cousins living in Adelaide, Helen, her two sisters and parents regularly travelled to Australia during her teenage years. It was always on the horizon that her family would join the Green clan in Australia.

In 2008, she and her partner, now fiancé, Matthew Felgate, who also trained as a geochemist, opted to complete their independent mapping projects in New Zealand. On the way home the pair made a quick trip to Melbourne to investigate the opportunities for postgraduate research in Australia. Both knew of the University of Melbourne’s School of Earth Sciences, which has a reputation for innovative research and teaching in the geological, climate and weather sciences. They met with Professor Janet Hergt, a geochemist and then Head of School of Earth Sciences and Jon Woodhead who cemented their desire to continue their research in Australia.

Science is part of the Green family DNA. Helen’s father, Tim Green, now a research and development Director with Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Parkville, inspired Helen to pursue a career in science. When Helen graduated from school, where she studied biology, geography, chemistry and physics, she was certain her career would involve science, but also wanted to work outdoors. Little did she expect that her Geology degree at the University of Durham in north east England, would lead her to fieldwork in the remote landscape of the Kimberley in north western Australia, and that she would be contributing to a multidisciplinary research project investigating the story of Australia’s first people.

In July 2009, just two days after graduating from the University of Durham with a (first class) Bachelor of Science (Geology) honours degree, Helen and her family left for Australia. At this point in her career Helen was most interested in the study of past climates (paleoclimates), and what better place for fieldwork than in the caves of Southern Australia. For anyone who has visited the caves at Naracoorte, a world heritage site, you will be familiar with its spectacular array of stalagmites, stalactites, straws, and flowstones. For her PhD, Helen used the uranium-thorium dating technique to measure the age of the cave rocks, collectively known as speleothems, to better understand past climates. She has also worked on samples from caves in Dominic Republic and South Africa.

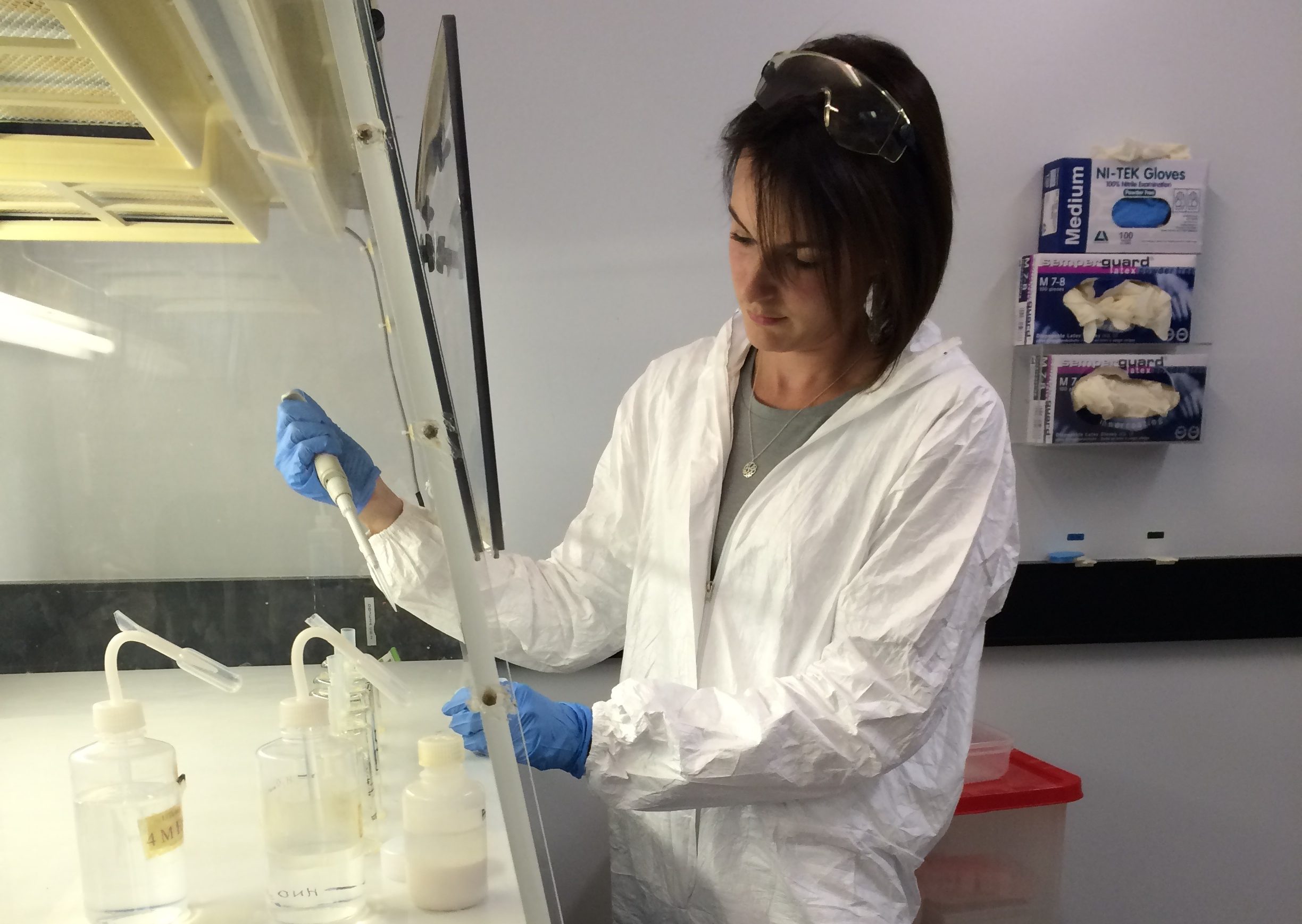

It was the application of chemistry to develop a scientific dating method for the speleothems that led her into her involvement with the Australian Rock Art Dating Project. As a post-doctoral research fellow, Helen spent three years developing, in partnership with Andrew Gleadow, an innovative way to marry the dating techniques explored in caves with a new methodology for the rock shelters in the Kimberley. As Helen has observed the dating technique was tried and tested in calcium carbonate formations found in limestone regions, but in the Kimberley the landscape is dominated by sandstone.

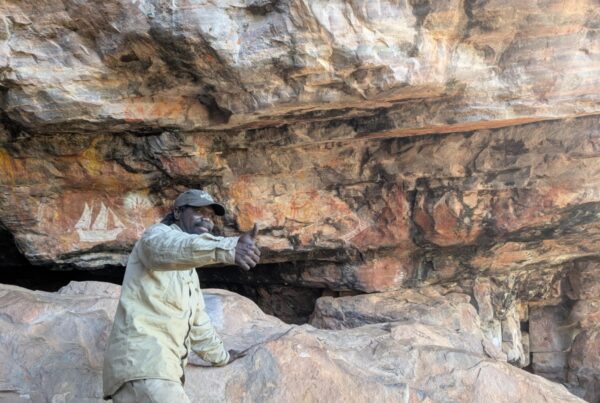

Helen’s first expedition to the Kimberley in 2015 was her first experience of camping and the Australian outback. Accompanied by a cook and other support staff, the scientists pitch their own tents and help to prepare the camp site. The expeditions are demanding, with each day beginning early with the scientists, investigators and indigenous partners travelling long distances to reach remote sites with the assistance of a helicopter. Helen relished the challenges. In one blog post she described her work:

My research focuses on characterising and dating the mineral accretions or ‘crusts’ we see fringing the rock art panels, varying in colour and texture from site to site. Uranium series dating works on the principle that the element Uranium, deposited within these crusts as they formed, decays to the element Thorium over a known amount of time. Using a mass spectrometer we can measure the amount of Thorium accumulated in the samples we collect and use this to calculate the age of the mineral deposit. Occasionally, these crusts are found under and/or over pigment allowing us to provide maximum and minimum bracketing ages for the associated paintings.

With each subsequent visit Helen has fine-tuned the processes both on site and back in the laboratory, and also developed an eye for the mineral accretions that might yield the best results. Working in a team of three, an archaeologist, indigenous representative/ traditional owner and a scientist, the sites are carefully recorded and documented. Each sample taken is recorded with meticulous care into the project database with a detailed set of photos and information regarding the motifs.

In the first three years of the project, Helen, new to Rock Art, and the history and culture of Aboriginal Australia, established a rapport and trust with project partners, in particular with Dunkeld Pastoral’s Cecilia Myers and the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation’s Ian Waina. The threesome travel to the sites together, each playing a fundamental and important role in identifying, recording and retrieving specimens. Over the next five years the slow and painstaking work of collecting and analysing data collected from field trips will bring new cultural knowledge. As part of this research Helen will continue to develop and adapt dating techniques for mineral coatings on rock art styles found in the Kimberley.

As Andy Gleadow has observed ‘What is exciting about this phase of the project is the new uranium series dating method will not just assist in bracketing the ages of rock art in the Kimberley, but also rock art more widely around the world where limestones do not exist.’

RAA acknowledges Ann Carew who spoke to Helen Green for this story; and the generous support of The Ian Potter Foundation for the RAA Fellowship in Rock Art Dating.