An organisation formed by a handful of passionate amateurs in the 1990s to study Kimberley rock art is evolving to further research in indigenous heritage

The Australian- Helen Trincia

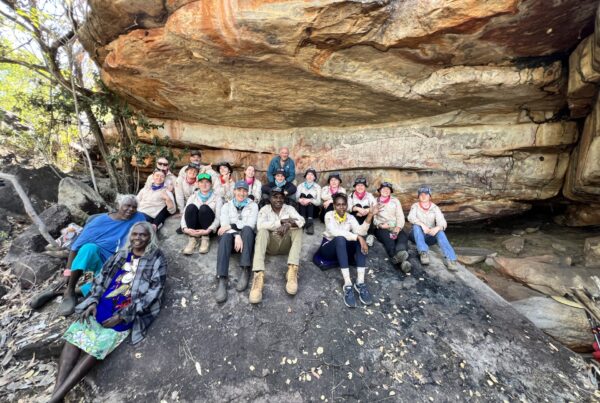

Traditional Owner Uriaha Waina and Cecilia Myers documenting Tassel Gwion figures in Drysdale River National Park. Picture: Mark Jones. Images supplied by Rock Art Australia. Picture credit: Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation

The Kimberley Foundation Australia has been a relatively small, if driven, philanthropic organisation over more than two decades.

With a head office in Collins Street, Melbourne it has some wealthy backers, a partnership with the Ian Potter Foundation, and boasts Australia’s best-known donor couple, Andrew and Nicola Forrest, among its official patrons. Even so, its work mapping and dating the Kimberley’s extraordinary rock art has been low key, with the focus on science rather than publicity. So when it changed its name this week to Rock Art Australia and indicated it would look beyond the Kimberley to the Pilbara, Arnhem Land and perhaps Indonesia, the change’s significance wasn’t immediately obvious.

Except that the evolution of the foundation, formed in the north of Western Australia by a handful of passionate amateurs in the 1990s, to an east-coast-based body keen to build a national profile, parallels a revolution in attitudes to indigenous heritage and the ancient art. The move to position itself to be the premier non-profit in this space dates back at least two years, well before the recent destruction of the Juukan caves in the Pilbara. But it comes as Juukan is seen as a turning point, a crisis that could push government to recognise the need to protect tens of thousands of cultural sites dating back at least 50,000 years.

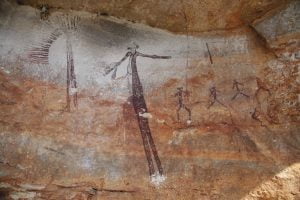

Polychrome Figures- Rock Art photographed in Drysdale River National Park, by Mark Jones. Images supplied by Rock Art Australia. Picture credit: Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation

The organisation’s chair, former Labor state and federal cabinet minister Laurie Brereton, says: “Historically the nation’s ancient rock art has been vastly undervalued. But the recent condemnation of Rio Tinto’s destruction of the Juukan caves has reverberated across Australia and around the world.

“The strong voices of Aboriginal leaders, the public outcry, the media attention, the condemnation by institutional investors, especially industry super funds, has sent a strong message to corporate Australia and beyond — people really care.”

Brereton has been on the board of the Kimberly Foundation, now RAA, for 14 years — a period in which it has grown from working with individual traditional owners to be much more involved with the formal indigenous peak bodies, such as the Kimberley Land Council. It’s been a period too when it has attracted some key business leaders, including the former Leighton boss, Wal King. The Forrests, who made their wealth from mining, are patrons and their charitable trust, Minderoo, is also a partner.

The RAA says it will stay focused primarily on the Kimberley but the broader remit inevitably involves change for a group which grew from contacts between Kimberley pastoralist Susan Bradley and four Ngarinyin traditional owners in the early 1990s.

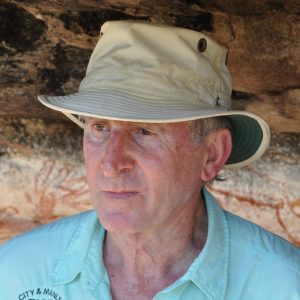

Laurie Brereton, board member Rock Art Australia

The men were concerned about preserving the valuable Wandjina sites in the far north of Western Australia and looked for help from non-indigenous locals. The men, now deceased, formed the Bush University in 1993 and four years later, Bradley and Christina Kennedy, a physiotherapist and farmer, set up the Wandjina Foundation, with two of the traditional owners on the board. In 2002 it was renamed Kimberley Foundation Australia and was listed on the Register of Cultural Organisations as a non-profit but it would be 2008 before it appointed a CEO and began to build an administrative base in Melbourne.

Back then, RAA was virtually the only group — beyond universities — interested in this research. It remains the only registered non-profit body dedicated to this work. Bradley is still on the board and continues to advocate strongly for scientists to work on the Wandjina sites which are still to be fully and widely dated.

In the past decade, the RAA has backed several major dating projects, including in the Drysdale River area of WA, working closely with the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation.

Nolan Hunter, the outgoing chair of the Kimberley Land Council, who has been on the RAA board for six years, says the name change recognises the science of rock art as part of a far bigger story of human habitation.

“You can’t limit the story to the Kimberley,” he says. Hunter joined the board as the KLC representative at a time when the council was keen to ensure that access by scientists to the sites, which are on native title, was legal and appropriate. He says the RAA has “turned itself around” and “understood they have to prioritise their engagement, engage with people on the ground to go out with the scientists”.

The interest of groups like the KLC in the research has grown with the recognition that rock art represents a valuable cultural and tourist resource.

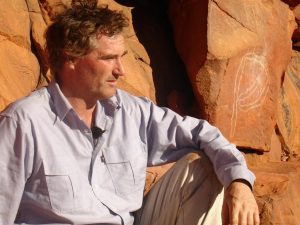

Peter Veth, professor of archaeology at the University of WA

Peter Veth, professor of archaeology at the University of WA and heritage advocate, says traditional owner groups have long asserted their connection to rock art, “but the tangible and intangible values have become universally and increasingly recognised in the past 10 or 15 years”.

“It’s ramped up with the increasing pressure from mining and the need to protect heritage values along with biodiversity,” he says. “As employment and health statistics have faltered, one of the critical things that people state matters to them is culture and heritage.”

The RAA does not promote tourism, but CEO Cas Bennetto says: “We want to support Aboriginal opportunities around rock art and everyone recognises it’s a drawcard for tourists. We can hand over all the scientific work that people have done to the (Aboriginal) corporations which have given permission for the research and that can be reworked (as) resources for tourists.”

Bennetto, CEO since 2010, says indigenous groups have recognised they must lead the research.

“In the past, it’s always been led by the scientists,” she says. “A German scientist would come and do research and leave and there would be no benefit (to the indigenous owners).”

Brereton says that Australians’ lack of awareness of the rich rock art in the north is due in part to its remoteness. This has also protected the art but he says indigenous groups are also taking care that tourism is developed carefully.

“It has not been a priority of indigenous owners to show it off for many good reasons” Brereton says. “That is starting to happen now. We are rapidly moving to a situation where white people driving utes and telling the story of 50,000-year-old indigenous culture with very little knowledge (will be replaced by) ventures involving indigenous experts in cultural knowledge and increasingly scientific knowledge.”

Prof Janet Hergt, traditional owner Augie Unghango and Prof Andy Gleadow. Picture: Mark Jones. Image taken in the field with permission of Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation.

Hunter sees a real opportunity for tourism thanks to the scientific work that has taken place over 20 years: “Can you imagine if the TOs (traditional owners) could have accredited training, academic training, to talk about their own rock art? Quite empowering and powerful.”

He says managed tourism would help avoid damage to rock art where people “are going in willy nilly, not realising they need to be respectful”.

Peter Veth says: “I think what you are seeing in this change of name, and the overhaul of heritage generally, is a much wider acknowledgment that the cultural values and assets of Western and Northern Australia are profound. It is becoming clear that numerous sites in WA are ancient, very well preserved, and have strong and ongoing traditional owner connections”. Juukan was a wakeup call of how “utterly irreplaceable” the records and contemporary connections are in the history of human people.”

Until recently, Veth, who has 40 years’ experience in the field, held the Kimberley Chair in Rock Art — the first of its kind — which was set up at UWA in 2013 after advocacy by RAA. The foundation leveraged $1.5 million from the Ian Potter Foundation, $500,000 from INPEX and matching funding from UWA.

In 2017, the RAA co-founded a similar chair in archaeological science at the University of Melbourne, this time with backing from the university’s chancellor, Allan Myers (whose wife Maria Myers chaired RAA for a decade and remains as deputy chair), the Minderoo Foundation and RAA’s contribution of $500,000.

Tassel Gwion Figures, Drysdale River National Park. Picture: Mark Jones. Image taken in the field with permission of Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation.

RAA says its work has resulted in more than $14m in funding. It provides seed funding for first-stage research, then stage-two funding for the creation of Australian Research Council linkage projects. The hope is that with a clear name and wider coverage it will attract more attention as Australians recognise the volume and significance of rock art.

But Veth says that while groups like the Pew Charitable Trusts have ramped up training of indigenous rangers, and mining companies are increasing their spend in this area, the research and preservation of significant cultural landscapes is still “radically underfunded” and indigenous groups “are still starved” for funds.

“Right across the Pilbara, groups are asking for quality installations where there could be interpretative material, visitor and study centres and where they could keep cultural material,” Veth says. “They have been requested for 40 years. Most foreigners, most international heritage people, can’t understand why there are not major regional displays and really obvious management of the assets.”

Traditional Owner Lucas Karadada and Damien Finch collecting a sample for Radiocarbon Dating. Picture: Pauline Heaney Images supplied by Rock Art Australia Photo credit: Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation

In a keynote speech at a forum in Fremantle last week held to debate proposed changes to the state’s Aboriginal heritage legislation that failed to save Juukan, Veth said that while the WA government set aside a reported $4m last year to ensure compliance by mining companies, resources profit in the state was about $172bn.

Says Veth: “There must be a mechanism to get more of that quantum, not just to manage the heritage, but to value-add and celebrate it.”

He says heritage management must move away from the piecemeal saving of sites in a “Swiss cheese” pattern to managing heritage in a cumulative sense. Areas which are agreed to be used, with free prior and informed consent, should have lower values and those that are “representative and highly significant” should be preserved as intact landscapes.

What of differences between traditional owners and scientists who want to work on archaeological and sacred sites?

Says Veth: “You will find some people saying it’s a competing paradigm (and it can be), but that’s not usually the case if properly set up. All the TOs, women and men, at the forum were repeatedly saying that they really valued working with heritage workers and the new knowledge it produced. When new artefacts and sites are found it usually helps profile how complex and diverse their mobs were.”

Traditional Owner Trinity Unghango and Professor Bert Roberts collecting samples. Picture: Pauline Heane. Image taken in the field with permission of Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation.

He says none of the speakers at last week’s forum affected by mining developments was anti-mining. Instead, the speakers acknowledged their reliance on regional economies. “They will accept a certain amount of land use but not at any price,” he says.

The language around ownership of heritage is also changing.

“Twenty years ago any question about post-indigenous values to the Australian country and internationally would usually have been scoffed at,” Veth says.

“But at the forum the PKKP (Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people who are Juukan’s traditional owners) actually said, this is heritage for us, but it is heritage for Australia and globally. They are positioning it now as both communal and global and that has become much more common.

“This material has value for indigenous owners but now in a multicultural Australia, that value is shared, in that people can share the space.

“There is a philosophical issue around whether that sense of place can be shared and become part of Australian identity without taking away the primary spiritual and land interests of Aboriginal Australians.”

It’s a challenging debate but without that sense of shared space, cultural heritage is out of sight and mind for many Australians.

Veth says government has not been able to support the documentation and protection needed and “funds and resources must be sequestered from industry land-users, who after all profit from the exercise. Why should taxpayers cross-subsidise FMG, BHP and Rio Tinto? It will also have to come from philanthropy, the research funding base, the community and even crowdsourcing.”

The new WA legislation is heading in the right direction, he says, but Australia needs a national strategy and national standards.

Nolan Hunter says: “I have spoken before about how we go some way to develop legislative frameworks to protect sites that have a couple of buildings a couple of hundred years old. But rock art that is thousands of years old could potentially use support.”