Rock art revelations. Scientific methods and Aboriginal knowledge are uncovering insights into the prehistoric settlement of northwest Australia.

It may be older than the 40,000 year-old paintings in Spain’s El Castillo cave, the world’s oldest well-dated rock art. It depicts human-like figures, a motif exceedingly rare in the rock art galleries of Europe, famed for their depictions of ice age animals, hand stencils and circles.

More remarkably, while Europe’s painted caves reflect long-gone traditions and people, the rock art of West Australia’s rugged, rust-coloured Kimberley reveals a complex thread running from the distant past to the present. “The rock art, particularly the detailed figurative rock art, in the Kimberley provides unique insights into Aboriginal cultures going back thousands and thousands of years,” says archaeologist Mike Morwood of the University of Wollongong. “What we see as researchers is evidence of continuity. There is change, but there is also continuity of art, beliefs and land use over thousands of years.”

According to Morwood, little research had been done in this archaeologically rich region until three years ago. That’s when a project called Change & Continuity: archaeology, chronology and art in the northwest Kimberley began. He co-leads the project, along with University of New England rock art archaeologist June Ross and Macquarie University dating expert Kira Westaway.

The multi-disciplinary group includes researchers from three universities and six graduate students. The project has approval from the Senior Traditional Owners from Wunambal Gaambera Country and Aboriginal rangers have developed skills in all aspects of the project.

The goal is to blend modern research techniques with traditional knowledge, not only to enhance archaeological understanding of the past but to assist traditional owners manage their land and culture into the future. The work will provide essential information on the distribution, age and content of cultural heritage sites across the vast region. The 2012 field season wrapped up late July and data analysis is underway. “We hope to make a limited visit next year, tidying up and conveying the results to the local communities,” Morwood says of the team which receives major funding from the Australian Research Council and the Kimberley Foundation Australia, along with additional in-kind support from the WA Department of Environment and Conservation, the Kandiwal Indigenous Community and aviation firm Slingair-Heliwork.

At the broadest level the Change & Continuity team seeks to document and date major turning points in the occupation of the Northwest Kimberley and answer fundamental questions. When did people first arrive? What impact did they have on local habitats and animals? How did they respond to climate changes?

“It will take generations to unravel it all,” predicts Ross. But like her colleagues she says details are emerging by combining archaeological excavation and dating techniques with the scientific analysis of the styles, techniques, positioning and functions played by the rock art.

Australian researchers have played a major role, along with French investigators, in putting rock art study into the mainstream of archaeology. Researchers worldwide now incorporate rock art into their investigations of prehistoric cultures. According to Morwood, they recognise that if they ask “the right questions” the art provides insight into the minds of people, not reflected in conventional artefacts.

As Ross notes, there’s a trove of rock art to interrogate in the Kimberley, from paintings and engravings to stone arrangements. “Where there’s water there’s rock art. The sheer volume and sheer variety is striking”. The team has recorded 210 rock art sites in detail and visited many others, mainly in the Lawley and Mitchell River catchments. “There must be hundreds of thousands of paintings in the region”,says Ross.

Imagine tall thin figures with tasseled belts, fancy headdresses and spears. Know originally as Bradshaws, after Joseph Bradshaw who reported them in 1891, these exquisite and highly detailed paintings are known now by their Aboriginal name, “Gwion”, and are an early regional style. The most recent works, unique to the Kimberley, come from the “Wanjina” period. Here, round white faces with large carbon black eyes and dark halos around their heads stare from the rock.

While it was argued by the late Kimberley rock art researcher Grahame Walsh that the two styles were so different, they must have been painted by people from different cultures, the new work shows otherwise.

“What we’re finding is the changes are gradual,” explains Ross. “We see shared attributes on many figures,” she says. As with other KFA sponsored research, the transition over time from one form to another becomes evident.

The team also sees artistic connections with the rock art of Arnhem Land to the northeast. And they’re confident information discovered during their excavation of seven rock shelter sites and three open sites near shelters will help establish how the people of the northwest Kimberley connected to those from the southern Kimberley. There, archaeologists have evidence of what may be a painted limestone slab dated to roughly 34,000– 43,000 before present.

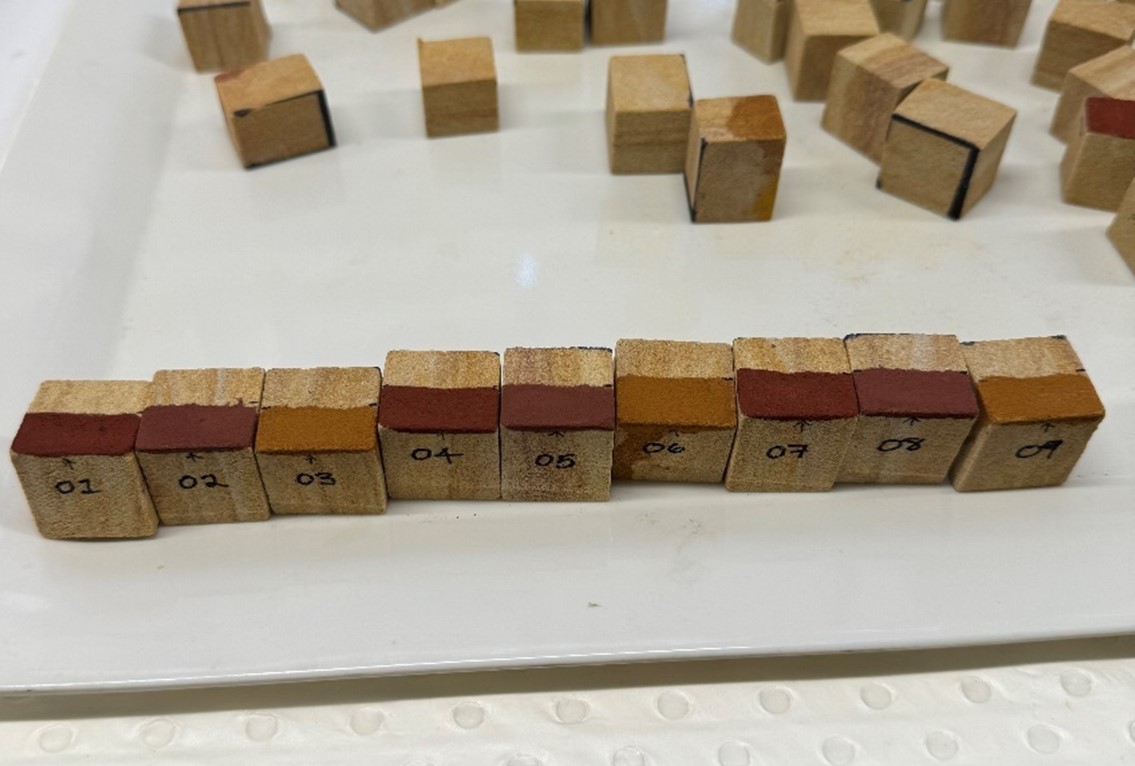

The critical task is to obtain more solid dates for the rock art and archaeological sites of the northwest Kimberley. To that end, tiny samples of ochre and other natural material – wasp nests, crusts and grains of carbon or sand – at the sites and above the art are being dated, using a variety of laboratory techniques.

So when were artists putting ochre on rock? So far, the evidence Westaway and her geochronologist colleagues have obtained suggests the peak of Wanjina production was 1500 to 500 years ago.

And the more ancient Gwions? “Mike and I know people were living the northwest Kimberley at least 36,000 years ago,” says Ross. She and Morwood note that University of Wollongong dating expert Maxime Aubert is testing samples right now that may push the age of the art back beyond 40,000 years. In a scientific twist, Aubert is using the same technique used to date El Castillo’s red handprints and disks. Expect headlines worldwide when the team’s paper hits the scientific press