But all that looks like changing, thanks to the work of the Kimberley Foundation Australia and its partners at several universities around the country and with Aboriginal Corporations.

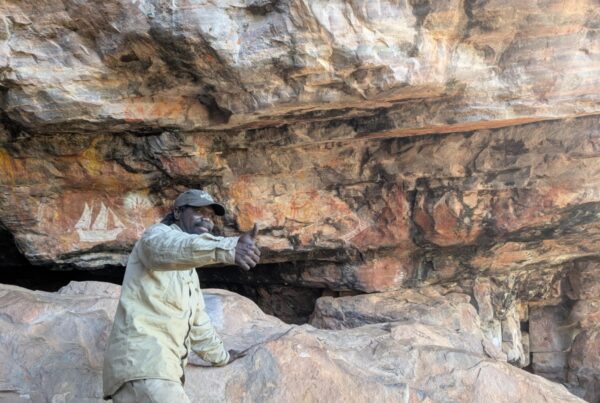

And thanks to the work of Ian Waina. Growing up in the north-east Kimberley in Western Australia, the rock art has long been Waina’s passion. Now, at 32, he is at the forefront of work aimed at preserving it and helping scientists date it so we can know more about who painted it and when.

Ian Waina.

“As an Aboriginal person we all have to play our role in looking after our art,” Waina tells me on the phone from the Kimberley. “I would rather share it than keep it [to ourselves].”

For a decade Waina has worked with the Kimberley Foundation Australia, a not-for-profit organisation established to research and preserve Kimberley rock art. He travels to the many sites of the art with Indigenous elders, scientists and with small tour groups. He is a veteran in the field: he has been guiding people to the art since he was at school.

He has visited many of the thousands of rock art sites, rock paintings and engravings on sandstone outcrops and escarpments, artefacts and stone arrangements, which are found across a landmass the size of Germany.

Waina believes the rock art is a priceless window to the lives of those who lived in the Kimberley tens of thousands of years ago. “Every rock art painting tells the story of what happened in the area,” he says.

“Some let you know what animals lived then, what was good for eating, others are a prophecy. The paintings are like diaries. That is how people told their stories.”

Just days after we spoke, Waina left on a five-week field mission accompanying scientists to rock art sites to test the art’s age through various carbon-dating and other techniques.

There are tens of thousands of rock art sites in the Kimberley providing, what the foundation says is, “primary evidence about how, when and why people first arrived in Australia” giving clues to “cultural beliefs, [and] how they lived and adapted to changing climactic conditions”.

It notes that the rock art is the only record of how people saw themselves, each other, the natural world and the social systems that they made. “It is one of the largest figurative bodies of art to survive anywhere on the planet, and yet so little is known about it.”

Waina’s role and that of many of the traditional owners in the massive Kimberley area have been critical in establishing the location of the art and whether it needs maintenance. “Some areas are safe,” he says. “Others are at risk through fire.” He knows the importance of caring for these sites. “Older people are telling me to look after it and keep the story going and the fire burning,” he says.

His work with scientists is an invaluable scientific and cultural collaboration. “I teach them traditional stories and they teach me about scientific ways of looking at it,” he says.

The Kimberley Foundation Australia is at the centre of research into dating and preserving the rock art. It is critical work. “All the rock art-related research we fund, the alliances with universities and scientists, and the collaborations with the Aboriginal Corporations is aimed at keeping culture strong for future custodians and informing the conservation and management of this priceless world heritage,” the foundation’s chief executive Cas Bennetto says. “The importance of the work cannot be overestimated. It’s for future custodians and generations of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and the world.”

Bennetto says we now know from the work of archaeologists that people have been in the Kimberley for 55,000 years. “They were people with developed aesthetic skills and they painted this highly distinctive rock art,” she says. “The rock art paintings are helping us resolve some of the big questions in world archaeology.”

Kimberley Foundation Australia’s deputy chairman Maria Myers first visited the Kimberley in 1995, using a helicopter to move around looking at rock art. “What we were shown was something quite extraordinary,” she tells me in the foundation’s office in Collins Street. “This is Australia’s story. When were they painted? And what was the culture that produced them?”

Myers says work is underway to discover through the art the story of the era. One major theory is based around climate change. “As the ice age settled on us the sea levels rose and 200 kilometres of country was inundated, so people had to move and it became drier,” she says. “Changes in the art are caused by changes in the climate. That’s the hypothesis that’s up for testing at the moment.”

Myers’ interest in this field began in the 1970s.

“When I started, people never knew what I was talking about,” she says.

Myers would like to see a greater connection by Australians to the extraordinary archaeological discoveries on our doorstep and the efforts to preserve them.

“It’s Australia’s story,” she says. She fears that Australians “don’t understand their own country and the people who lived here, and [need to] take it on as their culture, and understand the history of contact between Aboriginal and white Australia”.

Says Cas Bennetto: “It is first and foremost an Indigenous people’s story but one with which non-Indigenous Australians identify and in which they take pride.”

This story first appeared in Domain. It is reproduced here with a minor correction.