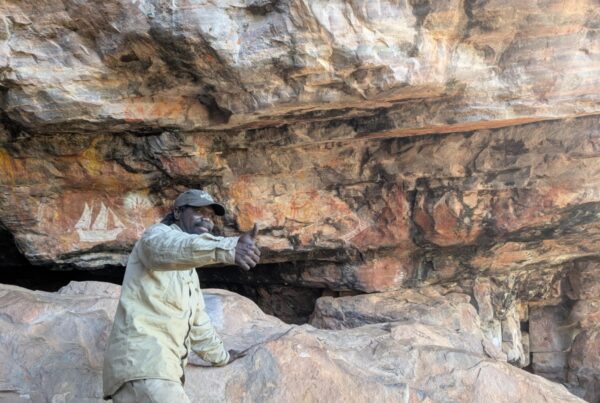

Prof Peter Veth, a leading expert in Indigenous archaeology was appointed as the inaugural Kimberley Foundation Ian Potter Chair in Rock Art at The University of Western Australia in November 2012. Since taking up the position in 2013 he has contributed significantly to research, teaching and public outreach initiatives. He has established collaborative partnerships between industry, Aboriginal communities and academia including securing major ARC Linkage projects. In this Q&A Peter reflects on the challenges and achievements in archaeology and rock art over the 5-year period.

How and when did you first get interested in Archaeology?

I was fascinated by the study of cultures as a child. I originally studied archaeology and anthropology with the foundational scholars Ronald and Catherine Berndt. My passion for archaeology was fuelled as a student doing remote fieldwork with researchers during the late 1970s and 1980s in the Kimberley, Pilbara and Western Desert including a year with the African rock art specialist Patricia Vinnicombe on the rock art of the Burrup (Murujuga). I completed my Honours project there in 1982 and my PhD in 1990 on the archaeology of the Martu peoples of the Canning Stock Route. These trajectories have now led back to a focus on the Kimberley and the privilege of working on one of the greatest rock art estates.

What do you see as the big challenges to be tackled in the next few years?

Dating art both on and off the rocks represents a major task over the next decade. A big challenge is systematically mapping rock art at the larger regional level to understand how style phases are both shared and differentiated through time as part of the identity making. A range of dating techniques being used such as OSL (Optically Stimulate Luminescence and the Uraniumseries dating ) will likely push back the known time of occupation in the Kimberley to greater than 50,000 years ago.

Other significant challenges are how to meaningfully link social, symbolic and subsistence behaviours with Quaternary records of changes in climate, environment and landscape; and documenting lifeways through deep time to the present.

Since you’ve been in the Chair, what strikes you as the most remarkable advances in knowledge?

a) The oldest dates from Northwest Australia are now in the 50,000 year range at the sites of Carpenter’s Gap and Riwi (in the Devonian reefs), Parnkupirti (at Lake Gregory) and Minjiwarra on the Drysdale River;

b) The oldest edge-ground axe technology in the world has been documented to 49–46,000 years ago;

c) The ongoing dating of earlier rock art style phases, including Naturalistic and Gwion figures, now plausibly extends into the Pleistocene era (older than 10,000 years ago);

d) Modelling shows that the extended banks of the Kimberley coastline, which were exposed during lower sea levels, could be seen from parts of West Timor and Roti and boated to;

e) Ornamental and ceremonial objects such as the ground nose peg and shell beads date from 46,000 to 30,000 years ago; and

f) The evidence for continuity of groups persisting through the aridity of the Last Glacial period is growing.

Can you yet explain the radically different types of art found in the Kimberley, the Pilbara and Arnhem Land?

These areas have people who have exercised different ways of marking country, expressing their world views and signaling identity. In rock art these may be identified as Style Provinces.

There are regional differences also with engravings on dark volcanic rocks in the Pilbara in contrast to pigments applied to the sandstones of the north-west. Kimberley and Arnhem Land people share the same ‘Tropical’ language family and some art forms; Pilbara people belong to a different language family and have cultural connections to the desert. All three areas show significant changes in the styles of art production through time.

Early styles of engraving in the Pilbara include very complex intaglio designs of humans, animals and mythological beings. These appear very different to later figures. Conventions and styles change through the millennia where art has preserved and this is a common pattern from all three Style Provinces.

How has the Kimberley Foundation Ian Potter Chair provided new platforms to promote studies of rock art and engage with the public and the Academy?

The research, promotional and advocacy work I am able to undertake in the role of Chair is considerable. The ARC Linkage projects which have been seed funded and supported by RAA are yielding mutually beneficial collaborations, partnerships and opportunities which see diverse groups working together for shared interests like land management, research outputs, education, tourism, conservation, and indigenous capacity building. The combination of all of these is promoting a greater appreciation of Kimberley Rock Art at regional, national and international levels. A Kimberley rock art research hub has been created at UWA that is building alliances nationally and internationally. Research training is significant with four PhD and Honours candidates currently working on Kimberley topics.

Over the last five years I have had the opportunity to make presentations to the public through films, television and news media reports and to large public festivals such as Woodford. I’ve worked with a wide range of people based at universities, museums and Aboriginal communities and been invited to make presentations at hunter-gatherer and rock art conferences in Glasgow, Mendoza, Taos, Vienna and Salzburg and World Heritage meetings in Africa, Scandinavia, USA and Europe and throughout Australia.

The Chair established by RAA, The Ian Potter Foundation, INPEX and the University enables us to promote a widespread understanding of our past which will in turn help shape Australia’s future.